mirror of

https://github.com/XRPLF/clio.git

synced 2025-12-05 08:48:13 +00:00

Updated backend README.md with the latest Cassandra schemas (#170)

* Updated backend README.md with the latest Cassandra schemas

This commit is contained in:

@@ -1,174 +1,132 @@

|

||||

The data model used by clio is different than that used by rippled.

|

||||

rippled uses what is known as a SHAMap, which is a tree structure, with

|

||||

actual ledger and transaction data at the leaves of the tree. Looking up a record

|

||||

is a tree traversal, where the key is used to determine the path to the proper

|

||||

leaf node. The path from root to leaf is used as a proof-tree on the p2p network,

|

||||

where nodes can prove that a piece of data is present in a ledger by sending

|

||||

the path from root to leaf. Other nodes can verify this path and be certain

|

||||

that the data does actually exist in the ledger in question.

|

||||

# Clio Backend

|

||||

## Background

|

||||

The backend of Clio is responsible for handling the proper reading and writing of past ledger data from and to a given database. As of right now, Cassandra is the only supported database that is production-ready. However, support for more databases like PostgreSQL and DynamoDB may be added in future versions. Support for database types can be easily extended by creating new implementations which implements the virtual methods of `BackendInterface.h`. Then, use the Factory Object Design Pattern to simply add logic statements to `BackendFactory.h` that return the new database interface for a specific `type` in Clio's configuration file.

|

||||

|

||||

clio instead flattens the data model, so lookups are O(1). This results in time

|

||||

and space savings. This is possible because clio does not participate in the peer

|

||||

to peer protocol, and thus does not need to verify any data. clio fully trusts the

|

||||

rippled nodes that are being used as a data source.

|

||||

## Data Model

|

||||

The data model used by Clio to read and write ledger data is different from what Rippled uses. Rippled uses a novel data structure named [*SHAMap*](https://github.com/ripple/rippled/blob/master/src/ripple/shamap/README.md), which is a combination of a Merkle Tree and a Radix Trie. In a SHAMap, ledger objects are stored in the root vertices of the tree. Thus, looking up a record located at the leaf node of the SHAMap executes a tree search, where the path from the root node to the leaf node is the key of the record. Rippled nodes can also generate a proof-tree by forming a subtree with all the path nodes and their neighbors, which can then be used to prove the existnce of the leaf node data to other Rippled nodes. In short, the main purpose of the SHAMap data structure is to facilitate the fast validation of data integrity between different decentralized Rippled nodes.

|

||||

|

||||

clio uses certain features of database query languages to make this happen. Many

|

||||

databases provide the necessary features to implement the clio data model. At the

|

||||

time of writing, the data model is implemented in PostgreSQL and CQL (the query

|

||||

language used by Apache Cassandra and ScyllaDB).

|

||||

Since Clio only extracts past validated ledger data from a group of trusted Rippled nodes, it can be safely assumed that these ledger data are correct without the need to validate with other nodes in the XRP peer-to-peer network. Because of this, Clio is able to use a flattened data model to store the past validated ledger data, which allows for direct record lookup with much faster constant time operations.

|

||||

|

||||

The below examples are a sort of pseudo query language

|

||||

There are three main types of data in each XRP ledger version, they are [Ledger Header](https://xrpl.org/ledger-header.html), [Transaction Set](https://xrpl.org/transaction-formats.html) and [State Data](https://xrpl.org/ledger-object-types.html). Due to the structural differences of the different types of databases, Clio may choose to represent these data using a different schema for each unique database type.

|

||||

|

||||

## Ledgers

|

||||

**Keywords**

|

||||

*Sequence*: A unique incrementing identification number used to label the different ledger versions.

|

||||

*Hash*: The SHA512-half (calculate SHA512 and take the first 256 bits) hash of various ledger data like the entire ledger or specific ledger objects.

|

||||

*Ledger Object*: The [binary-encoded](https://xrpl.org/serialization.html) STObject containing specific data (i.e. metadata, transaction data).

|

||||

*Metadata*: The data containing [detailed information](https://xrpl.org/transaction-metadata.html#transaction-metadata) of the outcome of a specific transaction, regardless of whether the transaction was successful.

|

||||

*Transaction data*: The data containing the [full details](https://xrpl.org/transaction-common-fields.html) of a specific transaction.

|

||||

*Object Index*: The pseudo-random unique identifier of a ledger object, created by hashing the data of the object.

|

||||

|

||||

We store ledger headers in a ledgers table. In PostgreSQL, we store

|

||||

the headers in their deserialized form, so we can look up by sequence or hash.

|

||||

## Cassandra Implementation

|

||||

Cassandra is a distributed wide-column NoSQL database designed to handle large data throughput with high availability and no single point of failure. By leveraging Cassandra, Clio will be able to quickly and reliably scale up when needed simply by adding more Cassandra nodes to the Cassandra cluster configuration.

|

||||

|

||||

In Cassandra, we store the headers as blobs. The primary table maps a ledger sequence

|

||||

to the blob, and a secondary table maps a ledger hash to a ledger sequence.

|

||||

In Cassandra, Clio will be creating 9 tables to store the ledger data, they are `ledger_transactions`, `transactions`, `ledger_hashes`, `ledger_range`, `objects`, `ledgers`, `diff`, `account_tx`, and `successor`. Their schemas and how they work are detailed below.

|

||||

|

||||

## Transactions

|

||||

Transactions are stored in a very basic table, with a schema like so:

|

||||

*Note, if you would like visually explore the data structure of the Cassandra database, you can first run Clio server with database `type` configured as `cassandra` to fill ledger data from Rippled nodes into Cassandra, then use a GUI database management tool like [Datastax's Opcenter](https://docs.datastax.com/en/install/6.0/install/opscInstallOpsc.html) to interactively view it.*

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### `ledger_transactions`

|

||||

```

|

||||

CREATE TABLE transactions (

|

||||

hash blob,

|

||||

ledger_sequence int,

|

||||

transaction blob,

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY(hash))

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.ledger_transactions (

|

||||

ledger_sequence bigint, # The sequence number of the ledger version

|

||||

hash blob, # Hash of all the transactions on this ledger version

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY (ledger_sequence, hash)

|

||||

) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (hash ASC) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table stores the hashes of all transactions in a given ledger sequence ordered by the hash value in ascending order.

|

||||

|

||||

### `transactions`

|

||||

```

|

||||

The primary key is the hash.

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.transactions (

|

||||

hash blob PRIMARY KEY, # The transaction hash

|

||||

date bigint, # Date of the transaction

|

||||

ledger_sequence bigint, # The sequence that the transaction was validated

|

||||

metadata blob, # Metadata of the transaction

|

||||

transaction blob # Data of the transaction

|

||||

) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table stores the full transaction and metadata of each ledger version with the transaction hash as the primary key.

|

||||

|

||||

A common query pattern is fetching all transactions in a ledger. In PostgreSQL,

|

||||

nothing special is needed for this. We just query:

|

||||

To look up all the transactions that were validated in a ledger version with sequence `n`, one can first get the all the transaction hashes in that ledger version by querying `SELECT * FROM ledger_transactions WHERE ledger_sequence = n;`. Then, iterate through the list of hashes and query `SELECT * FROM transactions WHERE hash = one_of_the_hash_from_the_list;` to get the detailed transaction data.

|

||||

|

||||

### `ledger_hashes`

|

||||

```

|

||||

SELECT * FROM transactions WHERE ledger_sequence = s;

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.ledger_hashes (

|

||||

hash blob PRIMARY KEY, # Hash of entire ledger version's data

|

||||

sequence bigint # The sequence of the ledger version

|

||||

) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table stores the hash of all ledger versions by their sequences.

|

||||

### `ledger_range`

|

||||

```

|

||||

Cassandra doesn't handle queries like this well, since `ledger_sequence` is not

|

||||

the primary key, so we use a second table that maps a ledger sequence number

|

||||

to all of the hashes in that ledger:

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.ledger_range (

|

||||

is_latest boolean PRIMARY KEY, # Whether this sequence is the stopping range

|

||||

sequence bigint # The sequence number of the starting/stopping range

|

||||

) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table marks the range of ledger versions that is stored on this specific Cassandra node. Because of its nature, there are only two records in this table with `false` and `true` values for `is_latest`, marking the starting and ending sequence of the ledger range.

|

||||

|

||||

### `objects`

|

||||

```

|

||||

CREATE TABLE transaction_hashes (

|

||||

ledger_sequence int,

|

||||

hash blob,

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY(ledger_sequence, blob))

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.objects (

|

||||

key blob, # Object index of the object

|

||||

sequence bigint, # The sequence this object was last updated

|

||||

object blob, # Data of the object

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY (key, sequence)

|

||||

) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (sequence DESC) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table stores the specific data of all objects that ever existed on the XRP network, even if they are deleted (which is represented with a special `0x` value). The records are ordered by descending sequence, where the newest validated ledger objects are at the top.

|

||||

|

||||

This table is updated when all data for a given ledger sequence has been written to the various tables in the database. For each ledger, many associated records are written to different tables. This table is used as a synchronization mechanism, to prevent the application from reading data from a ledger for which all data has not yet been fully written.

|

||||

|

||||

### `ledgers`

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table uses a compound primary key, so we can have multiple records with

|

||||

the same ledger sequence but different hash. Looking up all of the transactions

|

||||

in a given ledger then requires querying the transaction_hashes table to get the hashes of

|

||||

all of the transactions in the ledger, and then using those hashes to query the

|

||||

transactions table. Sometimes we only want the hashes though.

|

||||

|

||||

## Ledger data

|

||||

|

||||

Ledger data is more complicated than transaction data. Objects have different versions,

|

||||

where applying transactions in a particular ledger changes an object with a given

|

||||

key. A basic example is an account root object: the balance changes with every

|

||||

transaction sent or received, though the key (object ID) for this object remains the same.

|

||||

|

||||

Ledger data then is modeled like so:

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.ledgers (

|

||||

sequence bigint PRIMARY KEY, # Sequence of the ledger version

|

||||

header blob # Data of the header

|

||||

) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table stores the ledger header data of specific ledger versions by their sequence.

|

||||

|

||||

### `diff`

|

||||

```

|

||||

CREATE TABLE objects (

|

||||

id blob,

|

||||

ledger_sequence int,

|

||||

object blob,

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY(key,ledger_sequence))

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.diff (

|

||||

seq bigint, # Sequence of the ledger version

|

||||

key blob, # Hash of changes in the ledger version

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY (seq, key)

|

||||

) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (key ASC) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table stores the object index of all the changes in each ledger version.

|

||||

|

||||

### `account_tx`

|

||||

```

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.account_tx (

|

||||

account blob,

|

||||

seq_idx frozen<tuple<bigint, bigint>>, # Tuple of (ledger_index, transaction_index)

|

||||

hash blob, # Hash of the transaction

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY (account, seq_idx)

|

||||

) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (seq_idx DESC) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

This table stores the list of transactions affecting a given account. This includes transactions made by the account, as well as transactions received.

|

||||

|

||||

The `objects` table has a compound primary key. This is essential. Looking up

|

||||

a ledger object as of a given ledger then is just:

|

||||

|

||||

### `successor`

|

||||

```

|

||||

SELECT object FROM objects WHERE id = ? and ledger_sequence <= ?

|

||||

ORDER BY ledger_sequence DESC LIMIT 1;

|

||||

```

|

||||

This gives us the most recent ledger object written at or before a specified ledger.

|

||||

CREATE TABLE clio.successor (

|

||||

key blob, # Object index

|

||||

seq bigint, # The sequnce that this ledger object's predecessor and successor was updated

|

||||

next blob, # Index of the next object that existed in this sequence

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY (key, seq)

|

||||

) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (seq ASC) ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

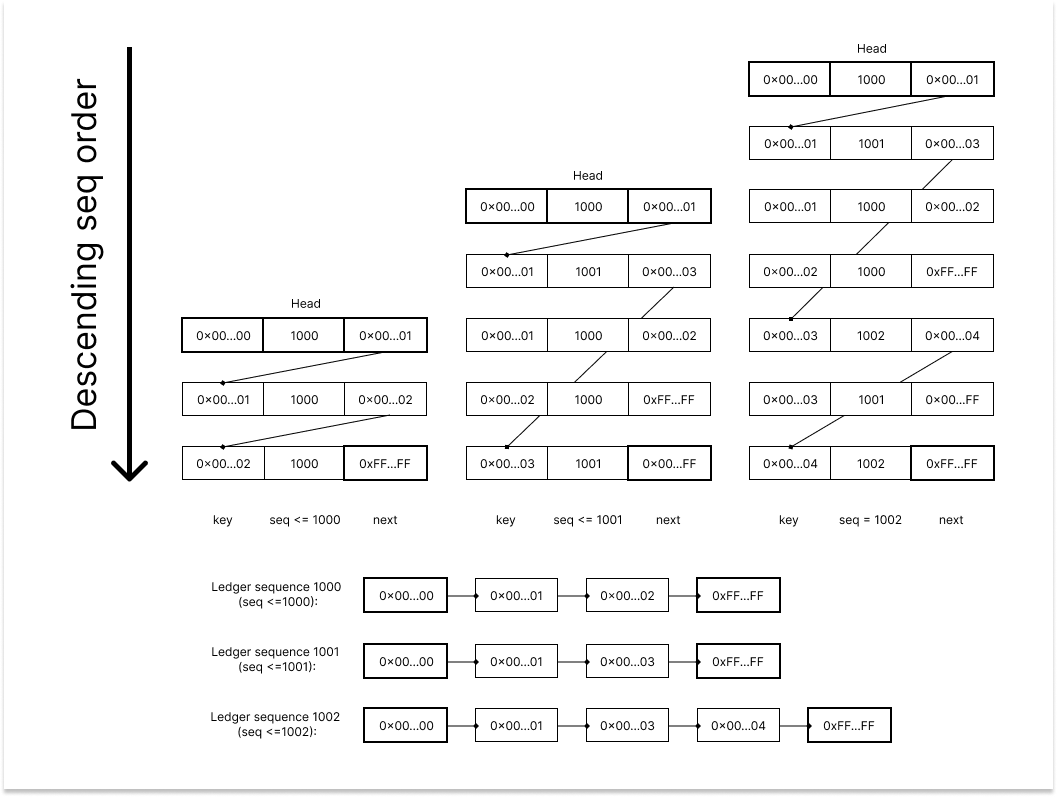

This table is the important backbone of how histories of ledger objects are stored in Cassandra. The successor table stores the object index of all ledger objects that were validated on the XRP network along with the ledger sequence that the object was upated on. Due to the unique nature of the table with each key being ordered by the sequence, by tracing through the table with a specific sequence number, Clio can recreate a Linked List data structure that represents all the existing ledger object at that ledger sequence. The special value of `0x00...00` and `0xFF...FF` are used to label the head and tail of the Linked List in the successor table. The diagram below showcases how tracing through the same table but with different sequence parameter filtering can result in different Linked List data representing the corresponding past state of the ledger objects. A query like `SELECT * FROM successor WHERE key = ? AND seq <= n ORDER BY seq DESC LIMIT 1;` can effectively trace through the successor table and get the Linked List of a specific sequence `n`.

|

||||

|

||||

When a ledger object is deleted, we write a record where `object` is just an empty blob.

|

||||

|

||||

*P.S.: The `diff` is `(DELETE 0x00...02, CREATE 0x00...03)` for `seq=1001` and `(CREATE 0x00...04)` for `seq=1002`, which is both accurately reflected with the Linked List trace*

|

||||

|

||||

### Next

|

||||

Generally RPCs that read ledger data will just use the above query pattern. However,

|

||||

a few RPCs (`book_offers` and `ledger_data`) make use of a certain tree operation

|

||||

called `successor`, which takes in an object id and ledger sequence, and returns

|

||||

the id of the successor object in the ledger. This is the object in the ledger with the smallest id

|

||||

greater than the input id.

|

||||

|

||||

This problem is quite difficult for clio's data model, since computing this

|

||||

generally requires the inner nodes of the tree, which clio doesn't store. A naive

|

||||

way to do this with PostgreSQL is like so:

|

||||

```

|

||||

SELECT * FROM objects WHERE id > ? AND ledger_sequence <= s ORDER BY id ASC, ledger_sequence DESC LIMIT 1;

|

||||

```

|

||||

This query is not really possible with Cassandra, unless you use ALLOW FILTERING, which

|

||||

is an anti pattern (for good reason!). It would require contacting basically every node

|

||||

in the entire cluster.

|

||||

|

||||

But even with Postgres, this query is not scalable. Why? Consider what the query

|

||||

is doing at the database level. The database starts at the input id, and begins scanning

|

||||

the table in ascending order of id. It needs to skip over any records that don't actually

|

||||

exist in the desired ledger, which are objects that have been deleted, or objects that

|

||||

were created later. As ledger history grows, this query skips over more and more records,

|

||||

which results in the query taking longer and longer. The time this query takes grows

|

||||

unbounded then, as ledger history just keeps growing. With under a million ledgers, this

|

||||

query is usable, but as we approach 10 million ledgers are more, the query starts to become very slow.

|

||||

|

||||

To alleviate this issue, the data model uses a checkpointing method. We create a second

|

||||

table called keys, like so:

|

||||

```

|

||||

CREATE TABLE keys (

|

||||

ledger_sequence int,

|

||||

id blob,

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY(ledger_sequence, id)

|

||||

)

|

||||

```

|

||||

However, this table does not have an entry for every ledger sequence. Instead,

|

||||

this table has an entry for rougly every 1 million ledgers. We call these ledgers

|

||||

flag ledgers. For each flag ledger, the keys table contains every object id in that

|

||||

ledger, as well as every object id that existed in any ledger between the last flag

|

||||

ledger and this one. This is a lot of keys, but not every key that ever existed (which

|

||||

is what the naive attempt at implementing successor was iterating over). In this manner,

|

||||

the performance is bounded. If we wanted to increase the performance of the successor operation,

|

||||

we can increase the frequency of flag ledgers. However, this will use more space. 1 million

|

||||

was chosen as a reasonable tradeoff to bound the performance, but not use too much space,

|

||||

especially since this is only needed for two RPC calls.

|

||||

|

||||

We write to this table every ledger, for each new key. However, we also need to handle

|

||||

keys that existed in the previous flag ledger. To do that, at each flag ledger, we

|

||||

iterate through the previous flag ledger, and write any keys that are still present

|

||||

in the new flag ledger. This is done asynchronously.

|

||||

|

||||

## Account Transactions

|

||||

rippled offers a RPC called `account_tx`. This RPC returns all transactions that

|

||||

affect a given account, and allows users to page backwards or forwards in time.

|

||||

Generally, this is a modeled with a table like so:

|

||||

```

|

||||

CREATE TABLE account_tx (

|

||||

account blob,

|

||||

ledger_sequence int,

|

||||

transaction_index int,

|

||||

hash blob,

|

||||

PRIMARY KEY(account,ledger_sequence,transaction_index))

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

An example of looking up from this table going backwards in time is:

|

||||

```

|

||||

SELECT hash FROM account_tx WHERE account = ?

|

||||

AND ledger_sequence <= ? and transaction_index <= ?

|

||||

ORDER BY ledger_sequence DESC, transaction_index DESC;

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This query returns the hashes, and then we use those hashes to read from the

|

||||

transactions table.

|

||||

|

||||

## Comments

|

||||

There are various nuances around how these data models are tuned and optimized

|

||||

for each database implementation. Cassandra and PostgreSQL are very different,

|

||||

so some slight modifications are needed. However, the general model outlined here

|

||||

is implemented by both databases, and when adding a new database, this general model

|

||||

should be followed, unless there is a good reason not to. Generally, a database will be

|

||||

decently similar to either PostgreSQL or Cassandra, so using those as a basis should

|

||||

be sufficient.

|

||||

|

||||

Whatever database is used, clio requires strong consistency, and durability. For this

|

||||

reason, any replication strategy needs to maintain strong consistency.

|

||||

In each new ledger version with sequence `n`, a ledger object `v` can either be **created**, **modified**, or **deleted**. For all three of these operations, the procedure to update the successor table can be broken down in to two steps:

|

||||

1. Trace through the Linked List of the previous sequence to to find the ledger object `e` with the greatest object index smaller or equal than the `v`'s index. Save `e`'s `next` value (the index of the next ledger object) as `w`.

|

||||

2. If `v` is...

|

||||

1. Being **created**, add two new records of `seq=n` with one being `e` pointing to `v`, and `v` pointing to `w` (Linked List insertion operation).

|

||||

2. Being **modified**, do nothing.

|

||||

3. Being **deleted**, add a record of `seq=n` with `e` pointing to `v`'s `next` value (Linked List deletion operation).

|

||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user